California Missions: Artistic and Architectural Legacy

|

| San Juan Capistrano Mission, late 19th to early 20th Century Unknown Photographer; San Juan Capistrano, California Photographic print; 4 3/8 x 7 1/2 in. 6867 Gift of Terry Elmo Stephenson, Jr. |

Breathing Life into the California Missions

The Spanish missions have bestowed an undeniable legacy of art and architecture upon California. However, without artists and organizations to advocate for their preservation, there would have existed no rich legacy to pass down through the generations.

In 1834, the mission system was officially abolished and secularized by the relatively new Mexican government, which signaled a shift in control away from the Franciscan order. Mexico intended to limit Spanish influence in its new territory, but, because the Spanish crown funded building materials and the salaries for the missionaries, this change also had the effect of decreasing both human and financial resources for the missions. The Mexican government was uninterested in spending money to preserve the missions. As a result, most fell into disrepair.

During the late 1800s, some, like Henry Chapman Ford with his sketches and Edwin Deakin with his watercolors, played a significant role in reviving the state’s Spanish heritage and championing a new architectural style that would come to be known as Mission Revival. Their work promoted California history by displaying the missions and their distinct Spanish structure. Indirectly, by showcasing the beauty of the missions they sparked an interest in restoring the structures to their original state. As such, organizations like the Landmarks Club were created to preserve historical Californian landmarks through repairing and renovating original mission architecture.

The above photograph of San Juan Capistrano was taken in the early 1890s shortly before the Landmarks Club began its restoration of the mission in 1896. The classical archways of the mission are crumbling in the image, and uncovered bricks peek out at the bases. Overgrown greenery threatens to encroach on the path. The mission in the photograph is in desperate need of restoration. Thanks to the work of the Landmarks Club, though, San Juan Capistrano did not waste away and is today part of the regional fabric.

|

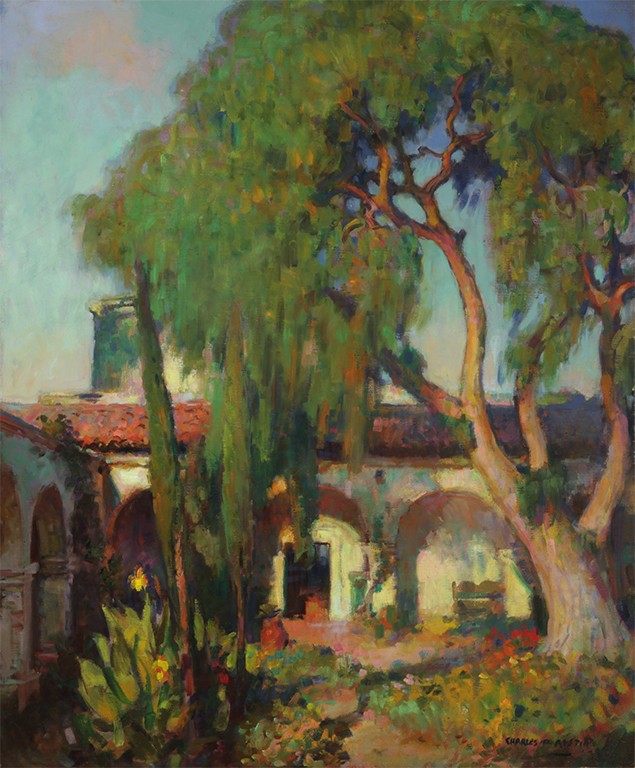

| The Great Pepper Tree, Mission San Juan Capistrano, 1928 Charles Percy Austin (American, 1883-1948); California Oil on canvas; 36 x 30 in. 32195B Gift of Mr. Ralph J. Steven |

Influential Qualities of Mission Architecture

Mission architecture was designed to imitate famous buildings in Spain, which themselves were originally inspired by Roman art and architecture. In fact, Mission Santa Barbara, founded in 1786, was influenced by the works of Vitruvius, a Roman architect who lived during the first century before the common era. Vitruvius thought that all buildings had to have three elements: strength, utility, and beauty; these components guided the design of the structures.

Charles Percy Austin’s painting of Mission San Juan Capistrano draws upon the beauty of the mission and its grounds. Compared to the state of the mission before the Landmarks Club restored it, San Juan Capistrano is alive in color and has a pleasant, manicured garden surrounding its walls. The painting is evidence of the importance of restoration of California’s historical landmarks, which offer both a history lesson and artistic inspiration to the public today.

The missions were mostly made from timber, stone, and adobe – materials that could be sourced from the environs surrounding the missions. Today, a few common attributes from the missions and its partner colonial institutions, presidios and pueblos, include red tiled roofs, stucco walls, and wrought iron gates. Entire towns like San Clemente in present-day California incorporate these characteristics into their architecture, reflecting a desire to recognize California’s Spanish roots. Furthermore, the historic portion of the Bowers Museum itself takes inspiration from Spanish mission architecture.

|

| Confirmation Class, San Juan Capistrano, 1897 Fannie Eliza Duvall (American, 1861-1934), California Oil on canvas; 27 x 37 x 3 in. 8214 Gift of Miss Vesta A. Olmstead and Miss Frances Campbell |

Integration of the Missions into Community Life

Over time, artists romanticized mission architecture and incorporated it into their own work. Here, Mission San Juan Capistrano in Duvall’s painting is the setting for a group of young girls ready to receive the sacrament of Confirmation. This mission especially grew popular from increased tourism from a railroad passing through the town of San Juan Capistrano.

Duvall’s Confirmation Class reflects the inclusion of missions in their local communities. The mission’s presence serves as an artistic supplement to the narrative of this piece rather than as a purely historical addition. During the late 1800s, depictions of the missions entered the artistic mainstream. Artists sought to capture a nostalgic tone in their work of the missions; Duvall did so by portraying the mission in an Impressionist style, one that is known for being inherently ephemeral.

|

| Glenwood Mission Inn, c. 1915 Putnam & Valentine, Los Angeles; Riverside, CA Paper; 7 x 9 in. 35196.1 Gift of Stella May Preble Nau Estate |

The Mission Inn

Perhaps the most well-known Mission Revival building is the Mission Inn in Riverside, California. Opened in the early 1900s, architect Arthur Benton was inspired by the growing popularity of the missions and designed the Inn in the Mission Revival style. A striking example of mission influence lies in the courtyard of the Mission Inn: a bell tower influenced by a similar tower at Mission San Gabriel. The Mission Revival architecture was in part also designed to attract tourists from the East Coast and the Midwest; tourists were even encouraged to imagine the Inn as if it was once an authentic mission.

The missions are the source of an artistic and architectural movement, one that continues to survive today. While they have a complicated history, the missions – along with California’s storied past – have nonetheless served as inspiration for countless creatives.

This post was researched and written by Grace Funk, an intern for the Bowers Museum. Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments