2002 North Main Street

Santa Ana, California 92706

TEL: 714.567.3600

The American Comic Strip and World War II

Content warning: The comics in this post are presented as originally created. They may contain outdated phrases and cultural descriptions which the Bowers Blog does not endorse.

|

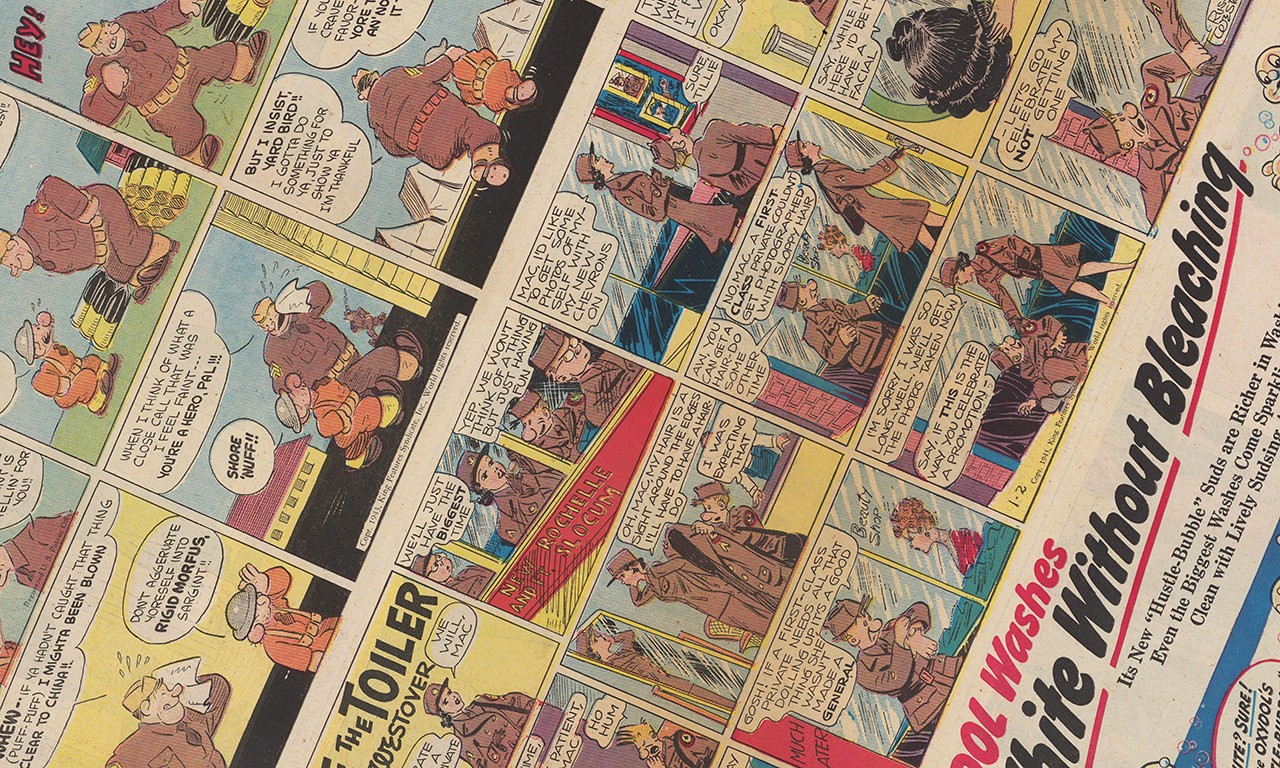

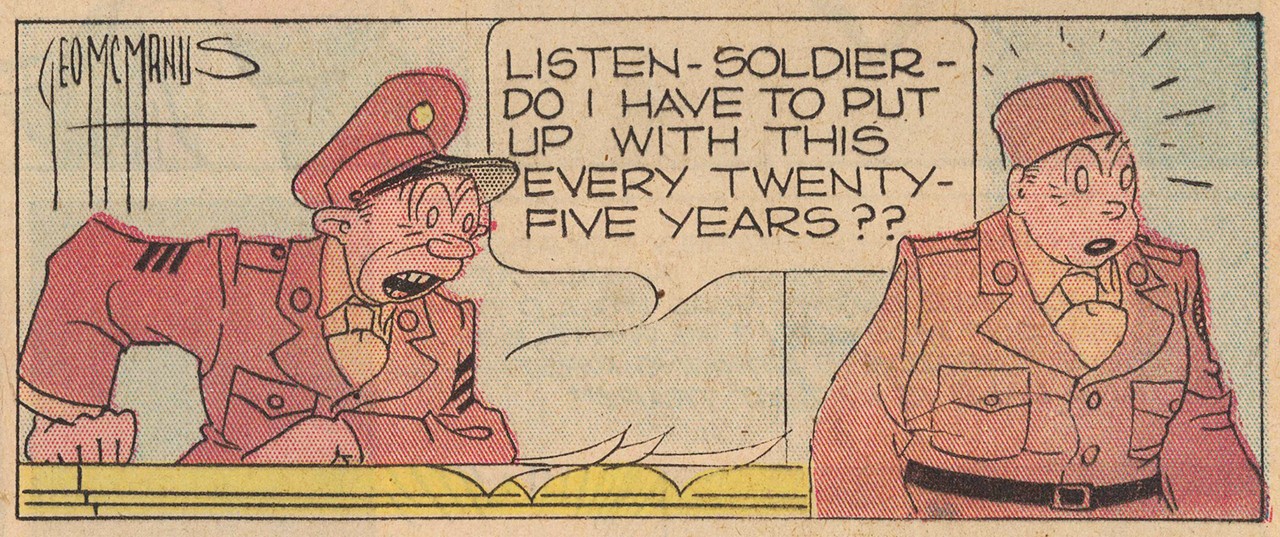

| Los Angeles Examiner’s “Puck: The Comic Weekly”, c. 1944 Hearst Communications; Los Angeles Paper and ink; 21 1/2 x 15 9/16 x 1/16 in. 40614.12 Gift of Mrs. Peryl Ashton |

Extra! Extra!

Organized by the Barbican Centre in London, the Asian Comics: Evolution of an Art Form exhibition is on display at Bowers Museum until September 8, 2024. This survey of one of the most popular mediums of entertainment in the world features an impressive array of both familiar and rare objects originating from all around Asia. In celebration of the exhibition, this Bowers Blog post analyzes another important development in sequential narrative art: the rise of American comic strips. Starting in the early 20th century, this type of entertainment was so popular in America that special newspaper editions with full pages dedicated to comics were regularly printed and distributed, typically on every Sunday. However, these special editions did not solely aim entertain. Amidst the humor one would expect from a comic, one might also find enticing advertisements, political commentaries, and targeted messaging. Throughout World War II (1939-1945), many comic artists incorporated war-time themes into the story lines and dialogue of their characters. Bowers’ permanent collection contains a selection of The Los Angeles Examiner’s “Puck: The Comic Weekly,” a once-a-week special edition dedicated to comics. In this post, we examine the beginnings of the American newspaper comic industry and the messaging found within World War II era comics, highlighting the incorporation of propaganda which influenced and educated the American public about the war.

|

|

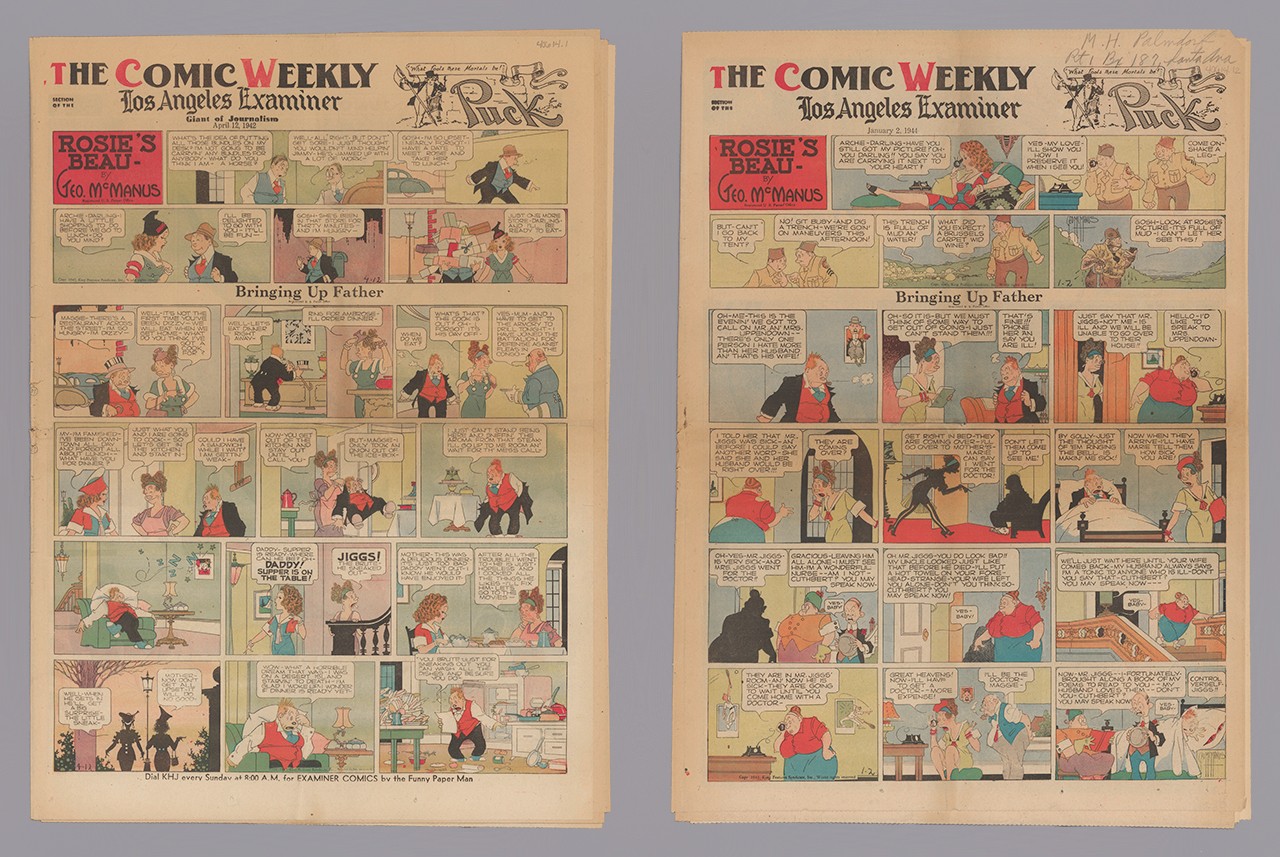

| Two Editions of Los Angeles Examiner’s “Puck: The Comic Weekly”, 1940s Hearst Communications; Los Angeles Paper and ink 40614.1,.12 Gift of Mrs. Peryl Ashton |

A Tumultuous Beginning

At the end of the 19th century, Joseph Pulitzer was the face of “new journalism” with his powerhouse of talented writers. His paper, New York World, featured sensational stories, excellent news reporting, and enticing editorials. It was the first newspaper to print a prominent comic section (with some in color) in the country, reaching national fame, in part due to the iconic artists under his employment. Pulitzer’s newspaper was nothing America had ever seen before, dominating the industry. However, in the 1890s, an ambitious William Randolph Hearst purchased The Journal, eager to make a name for himself in the New York newspaper industry. By the turn of the century, Hearst’s paper had overtaken Pulitzer’s reach and the two entered a vicious rivalry which Hearst effectively won through means such as poaching all of Pulitzer’s top comic artists.

The competition between Hearst and Pulitzer brought to light the massive potential of the “funny pages,” and forever changed newspapers into a medium of entertainment in the 20th century. Comic papers became longer, more colorful, and full of advertisements. Some of the most famous comic strips of all times, such as Popeye and Donald Duck, came out of this period. According to a Hearst Communications advertisement, by the 1940s, an estimated 20 million people were reading Hearst’s “Puck: The Comic Weekly,” making it an ideal vehicle for disseminating information to Americans as the United States entered World War II.

|

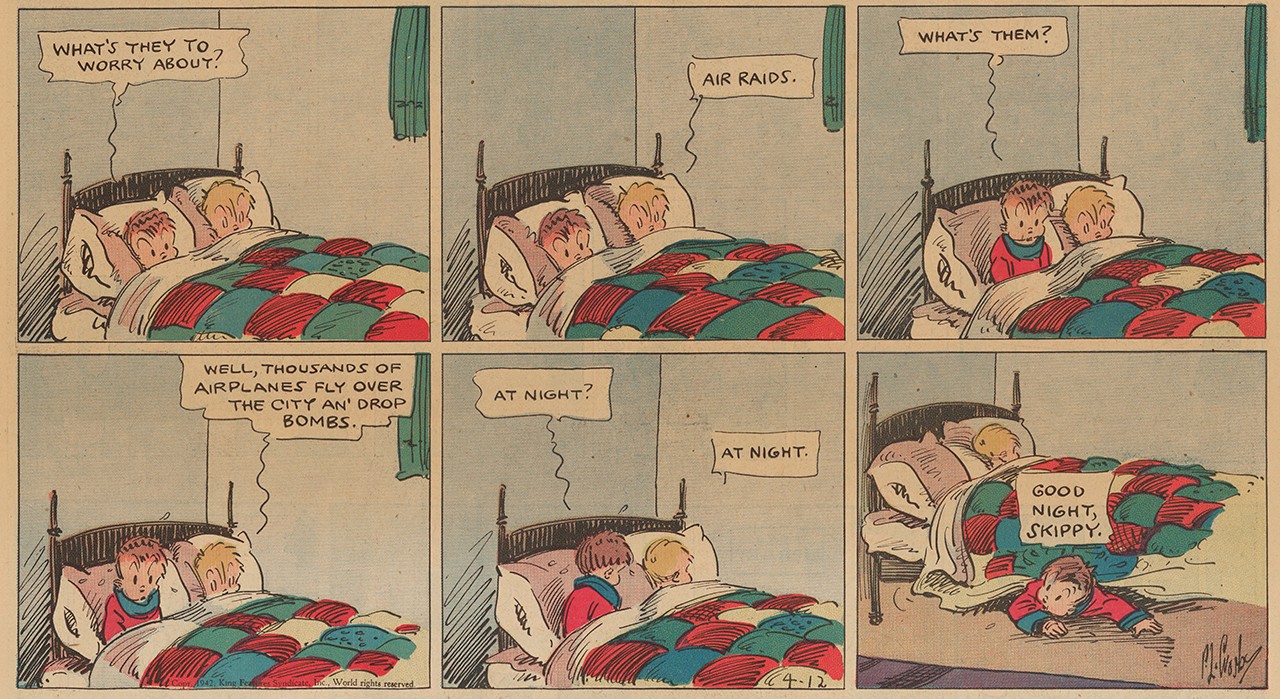

| “Skippy” in the Los Angeles Examiner’s “Puck: The Comic Weekly”, c. 1942 Hearst Communications; Los Angeles Paper and ink; 21 1/2 x 15 1/2 x 1/16 in. 40614.1 Gift of Mrs. Peryl Ashton |

|

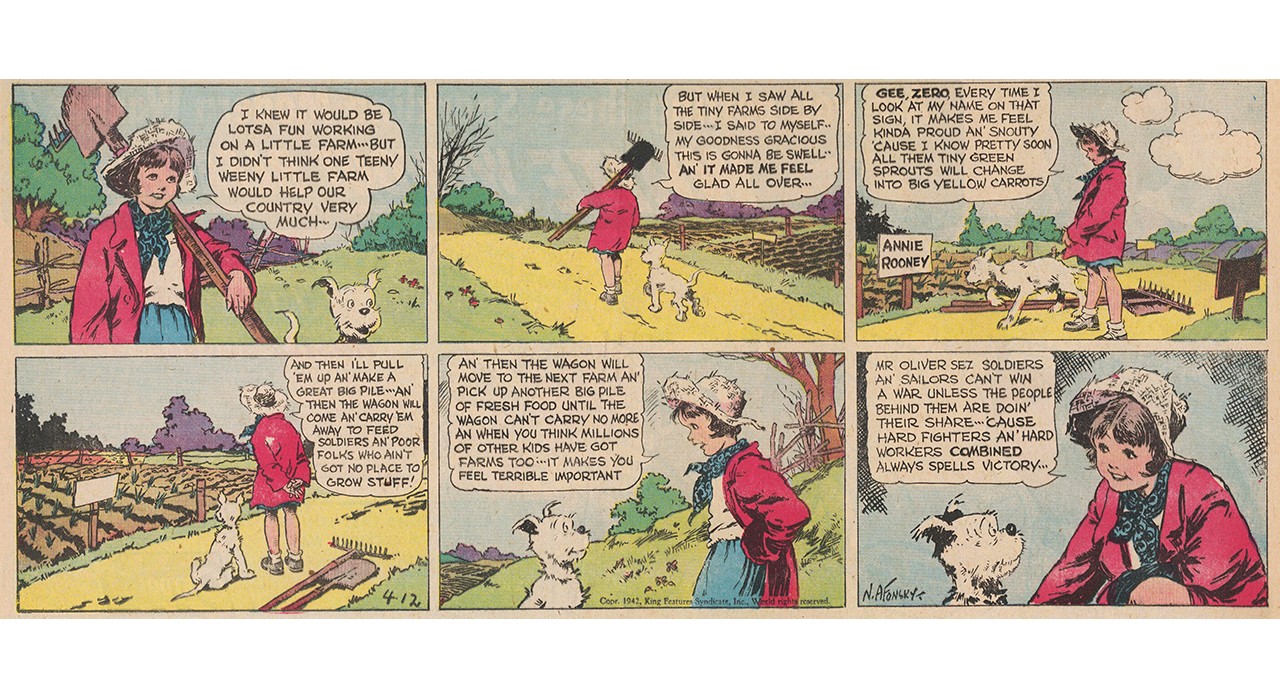

| “Little Annie Roonie” in the Los Angeles Examiner’s “Puck: The Comic Weekly”, c. 1942 Hearst Communications; Los Angeles Paper and ink; 21 1/2 x 15 1/2 x 1/16 in. 40614.1 Gift of Mrs. Peryl Ashton |

Entertainment, Education, or Maybe a Little of Both

In this 1942 installment of Skippy, two young boys engage in a conversation about the war, something they surely are modeling after the adult conversations around them. Skippy explains the definition of an air raid to his curious companion, and in doing so defines the phrase for the many young American readers. Little Annie Roonie, in the comic of the same name, tells her dog, Zero, of her excitement about participating in the war efforts by growing food for soldiers. Her small actions allow her to contribute and instill in her a sense of American pride. It is difficult to say whether young readers understood the concepts presented in these strips. However, it is clear that the medium was used to familiarize children with the war.

|

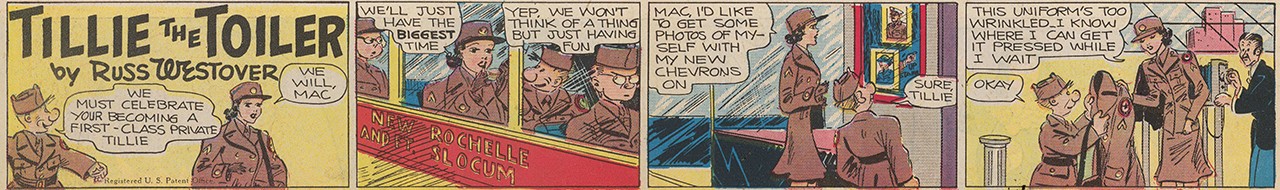

| “Tillie the Toiler” in the Los Angeles Examiner’s “Puck: The Comic Weekly”, c. 1944 Hearst Communications; Los Angeles Paper and ink; 21 1/2 x 15 9/16 x 1/16 in. 40614.12 Gift of Mrs. Peryl Ashton |

|

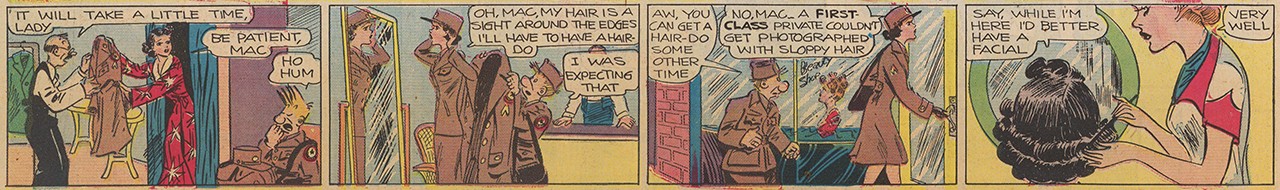

| “Tillie the Toiler” in the Los Angeles Examiner’s “Puck: The Comic Weekly”, c. 1944 Hearst Communications; Los Angeles Paper and ink; 21 1/2 x 15 9/16 x 1/16 in. 40614.12 Gift of Mrs. Peryl Ashton |

|

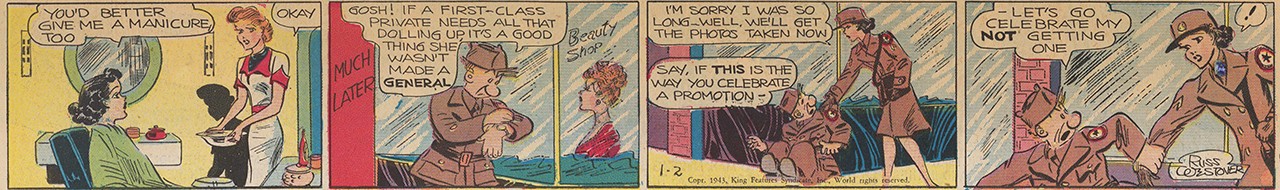

| “Tillie the Toiler” in the Los Angeles Examiner’s “Puck: The Comic Weekly”, c. 1944 Hearst Communications; Los Angeles Paper and ink; 21 1/2 x 15 9/16 x 1/16 in. 40614.12 Gift of Mrs. Peryl Ashton |

|

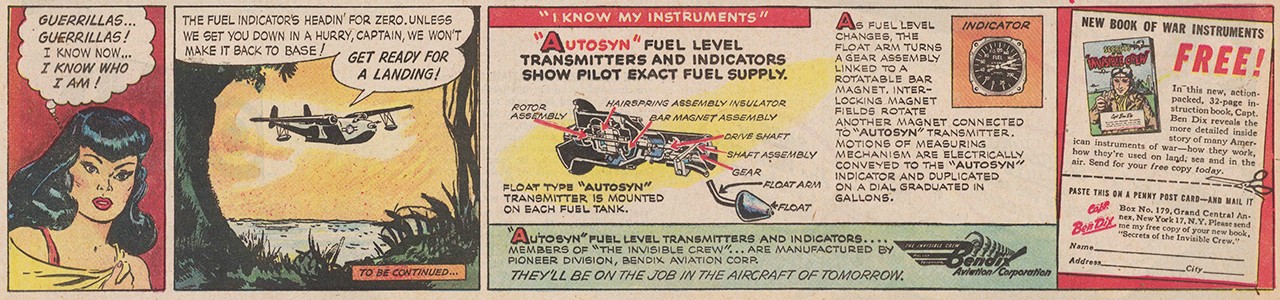

| “Captain Ben Dix” in the Los Angeles Examiner’s “Puck: The Comic Weekly”, c. 1944 Hearst Communications; Los Angeles Paper and ink; 21 1/2 x 15 5/8 x 1/16 in. 40614.35 Gift of Mrs. Peryl Ashton |

|

| “Captain Ben Dix” in the Los Angeles Examiner’s “Puck: The Comic Weekly”, c. 1944 Hearst Communications; Los Angeles Paper and ink; 21 1/2 x 15 5/8 x 1/16 in. 40614.35 Gift of Mrs. Peryl Ashton |

|

| “Captain Ben Dix” in the Los Angeles Examiner’s “Puck: The Comic Weekly”, c. 1944 Hearst Communications; Los Angeles Paper and ink; 21 1/2 x 15 5/8 x 1/16 in. 40614.35 Gift of Mrs. Peryl Ashton |

Off to War We Go

Tillie, the titular character of the comic strip Tillie the Toiler, is a model, secretary, and stenographer who shows her support for the war by enlisting in the Army, even receiving a promotion to first-class private. Captain Ben Dix, a comic produced by the Bendix Aviation Corporation, highlighted the action on the front lines as Captain Dix fights alongside the United States Air Force, all the while educating Americans old and young about the mechanics and operations of aircraft.

Ben Dix and Tillie’s adventures contributed to the war effort by surpassing the bounds of the comic strip. How? By inspiring young men and women to enlist. During WWII, over 350,000 women enlisted in the various branches of the military as service members in specialized women’s units. Tillie’s story tells women everywhere that they too can join the Women’s Army Corps. As for Captain Dix, his thrilling tales of adventure (and a helpful mail-order guide to Aircraft and the Army Air Force) were enough to directly encourage over 1,000 young men to enlist in the Air Corps Enlisted Reserves in 1944.

|

| “Rosie's Beau” in the Los Angeles Examiner’s “Puck: The Comic Weekly”, c. 1944 Hearst Communications; Los Angeles Paper and ink; 21 1/2 x 15 5/8 x 1/16 in. 40614.35 Gift of Mrs. Peryl Ashton |

An Industry Changed

The Writer’s War Board (WWB), an influential group of writers that helped federal agencies and the military disseminate propaganda during World War II, is known to have been involved both with the U.S. newspaper and comic book industries, making it possible that comic strip artists or “Puck the Comic Weekly” were influenced to create propaganda. However, given the small size of the WWB, their individual reach was limited. Why would so many different creators choose to address the war, and even encourage individuals to join in the efforts? The answer lies in part within the comic industry of the time. For Mr. Hearst and his media conglomerate Hearst Communications, his goal was to progress his domination of the newspaper industry. The popularity of comics provided the perfect avenue to maintain viewership of his paper, as drawing in readers and advertisers ensured that Hearst stayed profitable. For the artists, it is almost certain that the war was on the mind of every American during the time. Every American was subject to the propaganda of the war. The efforts of the United States’ messaging emphasized a united home front reliant on the unification of all citizens in both effort and ideology. Only then could the United States succeed in supporting a very costly war. The culture of American pride could in fact be enough to encourage these comic artists to include war time propaganda into their narratives. However, due to the myriad of artists involved, a variety of factors might have motivated them. Over 80 years later, we are left to reflect on how comic strips were and continue to be used to influence public opinion.

Guest written by Laura Chikami. Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments